From the Body to the Brain: Understanding our Nervous Systems with Polyvagal Theory

When I was first training in yoga therapy nearly a decade ago, the primary line of thinking about our autonomic nervous system, was that it could be broken down into two parts: the sympathetic nervous system (fight or flight) and the parasympathetic nervous system (rest and digest). The old school way of thinking about our yoga practice used to be focused on the parasympathetic nervous system and getting the body to rest. The recent research coming our on our nervous systems offers a much more nuanced understanding of our nervous system through Polyvagal Theory.

Neuroscientist Dr. Stephen Porges has added to the understanding of the complexity of our nervous system by suggesting that the autonomic nervous system actually has three parts. Depending on what our bodies pick up as either safety, danger, or a life threat (neuroception), and what internal sensations (interoception) and external cues (exteroception) are going on, automatic reactions, behaviors, and choices will take place. The biological reaction happens before we make the personal narrative, and often the way we make sense of the world is informed by these subtle biological sensations.

It is important to note that the way in which we react based on our neuroception are actually well functioning survival mechanisms that get framed as maladaptive coping skills. In truth, most people functioning poorly are actually just seeking safety.

What is Polyvagal Theory

The vagus nerve is the largest nerve in the parasympathetic nervous system and 80% of its fibers are sensory, which means it is mostly sending messages from the body up to the brain, not the other way around. The three parts of our nervous system according to Dr. Stephen Porges are:

1. Social Engagement System/Ventral Vagal/Also part of the parasympathetic branch.

When safe, this allows us to make eye contact and read people’s facial expressions and to co regulate with other humans through things like smiling and laughing. This part of our system allows for foraging, freedom, friendship and promotes health and growth by coregulating in community with others. It allows us to be cool, calm and collected, while accessing compassion and connection. When we are not safe, we can use this system for control, manipulation, passive aggressiveness, lying, denial.

Increase in blood flow to our skin, face and limbs. Oxytocin

Decrease in defensiveness

2. Sympathetic Nervous System/Mobilization response/hyperarousal.

When safe, this allows us to engage in teamwork, yoga, movement, art, exercise, creation, sex, play and sensuality. Often I find myself saying anxiety and excitement run on the same nerve endings. This is the place where we also experience excitement about a fun event or anxiety about family coming into town. When unsafe, we can engage in a fight response which can look like frustration, irritation, anger or rage. Or a flight response, which can look like worry, anxiety, fear and panic.

Increase in blood pressure, heart rate, pupil dilation, more airflow. Adrenaline, Cortisol.

Decrease in digestive function, fuel storage and insulin.

3. Parasympathetic Nervous System/Dorsal Vagal/Immobilization.

When safe this is our rest and digest response. It allows for things like meditation, trance states, hypnosis, and prayer. When unsafe and sensing a life threat, it can access feelings of helplessness, dissociation, numbness, trapped, hopeless, shut down, and shame. This is thought to be the oldest part of the parasympathetic system and operates below the diaphragm. It is our gut response so to speak. When sensing a life threat, it leads to total immobilization such as fainting, while conserving all vital life organ function, and a surge of endorphins allows for a higher threshold of pain. It also leads to fragmentation or dissociation, which allows us to in a sense leave our body in highly traumatic situations.

Increase in fuel storage and digestion. Endorphins.

Decrease in temperature, heart rate, blood pressure, muscle tone, memory, pupils constrict.

So why is this important?

We all have very different thresholds of tolerance for stress based in our genetics and past life experiences. Nervous system regulation or dysregulation can be highly contagious. By being either calm and in control of our nervous system or dysregulated, we impact and ripple out into our environment and community. We are designed to use the social engagement system to connect with others and to make eye contact to understand what is going on. If a small child runs up to a parent with a scraped knee, the mom’s calm collected nature often allows the child to settle swiftly. The child’s fear was more painful than the knee scrape itself. If the mom sees a shard of glass in her child’s knee and begins to cry or panic herself, then both the mom and the child might be panicked and it may take longer to settle.

This often happens in couples too. If one person is in their sympathetic nervous system and mobilized to fight or take action in response to stress, and the other one is more shut down and frozen, it is easy to feel like you are not on the same page with your partner. When we are chronically dysregulated, or not feeling safe, it’s very easy to misread someone’s fascial cues. For example, thinking your partner is mad at you, asking repeatedly if they are angry with you, and that badgering causing your partner to go into an equally dysregulated state or to shut down.

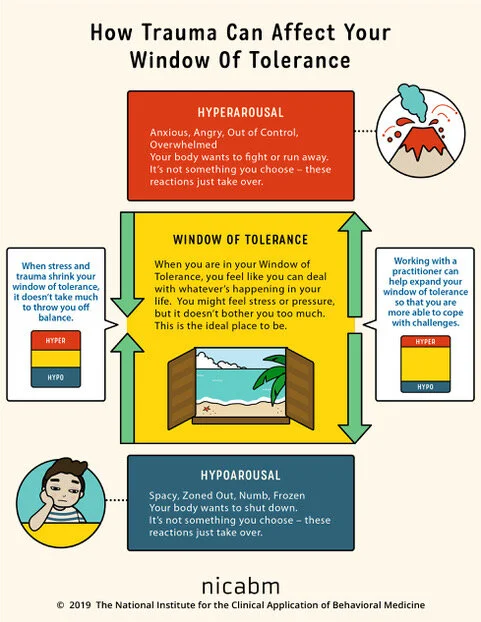

Dan Seigel talks about this as the window of tolerance. We all have a certain threshold of tolerance in our nervous system to be able to manage and mitigate stress. However, when we are triggered, some people move towards a hyper aroused state, while others move towards a hypoaroused state. Both are equally dysregulated states, they simply look very different. Our automatic reactions of the autonomic nervous system are just that, a knee jerk reaction.

But as we add more space, shifting from autopilot to manual override we can rewire the system to tolerate higher levels of stress and discomfort and we can restabilize more swiftly after a trigger. We can move both laterally and vertically through this system. Yoga and Mindfulness have both been proven to help improve vagal tone and heart rate variability. These are fancy terms for saying, when we break out of our window of tolerance or there is stress, how quickly we can recover and get back to a regulated state again. We are seeking not just homeostasis in landing in our parasympathetic nervous system, but rather a homeodynamic state to be able to move fluidly and swiftly through the system depending on the stimulus.

For tips and tricks on how to help settle the nervous system, check out this YouTube video on “Coping with the unknown”.

References & Resources

Amazing resources, click HERE

Porges, S. & Buczynski, R. Beyond the Brain: Using Polyvagal Theory to Help Patients “Reset” The Nervous System after Trauma. NICABM webinar series: Rethinking Trauma. 2014.

Dr. Stephen Porges. What is the Polyvagal Theory. PsychAlive.

Ogden, P., Minton, K., & Pain, C. (2006). Trauma and the body: A sensorimotor approach to psychotherapy. New York, NY, US: W W Norton & Co.

Siegel, D.J. (2012). The Developing Mind: How Relationships and the Brain Interact to Shape Who We Are. New York, USA: Guilford Press.

Resmaa Menakem. My Grandmother’s Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending our Hearts and Bodies. Central Recovery Press. 2017.

Matthias Schwenteck. Polyvagal Theory Dr. Stephen Porges.